Transportation is Nanaimo’s leading source of greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for 63% of total GHG emissions in 20171. One of the reasons for this insanely large number is the reliance on automobiles to get around town. Since the post-war home-building boom of the 50s and 60s, North America has been building its cities for cars, not people. This auto-oriented development pattern has cemented the need for a car in every resident’s mind. From grocery shopping to dentist appointments and everything in between. Nanaimo has sprawled out to the point of absurdity; whole neighbourhoods are kilometres away from the nearest commercial zone; our downtown experienced disinvestment as big-box commercial set up shop in the North-End of town; communities like Harewood lost their corner grocers as chain stores emerged. At the heart of all these issues was the insistence that cars were the future. That hasn’t exactly worked out for us.

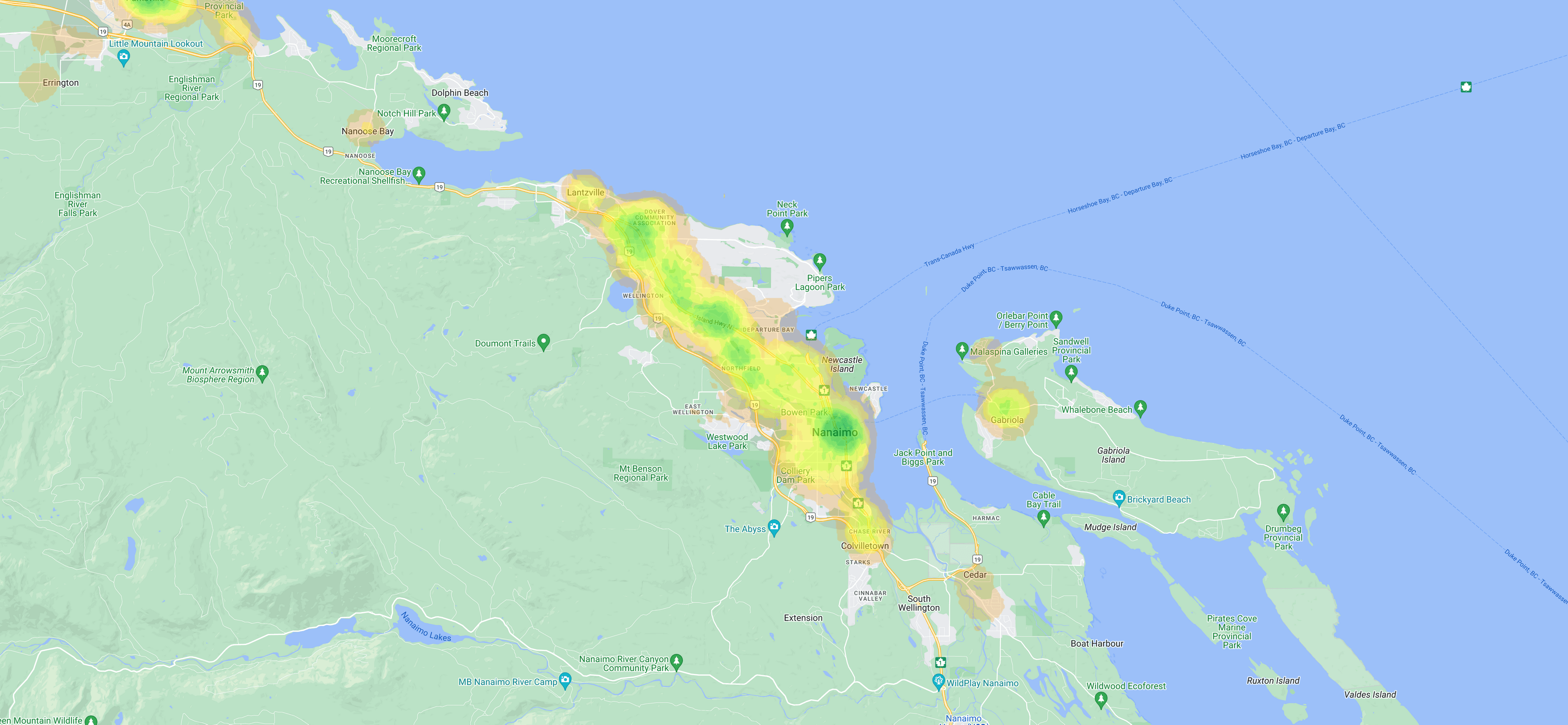

Nanaimo’s walkscore heatmap. Note the areas of the map with the darkest blobs – those are the few places in Nanaimo that you could realistically service your needs without a car. (Walkscore)

Nanaimo’s walkscore heatmap. Note the areas of the map with the darkest blobs – those are the few places in Nanaimo that you could realistically service your needs without a car. (Walkscore)

“The farther our homes are from our places of work, schools, and amenities, the more driving we all need to do and the more emissions we generate,” says Heather Baitz, Chair of the Nanaimo Climate Action Hub. “NCAH is in favour of smart urban planning to create communities where our daily needs are close by. Combining that design with safe and reliable walking and rolling infrastructure and frequent public transit will allow us to reduce emissions.”

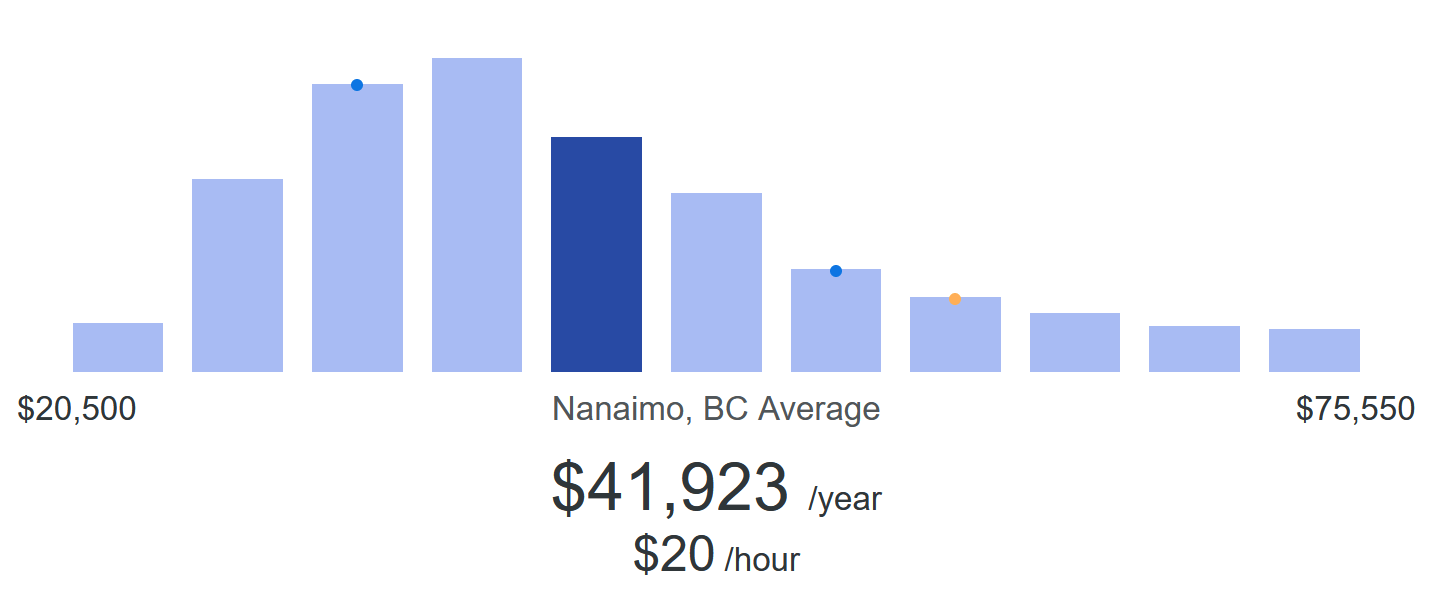

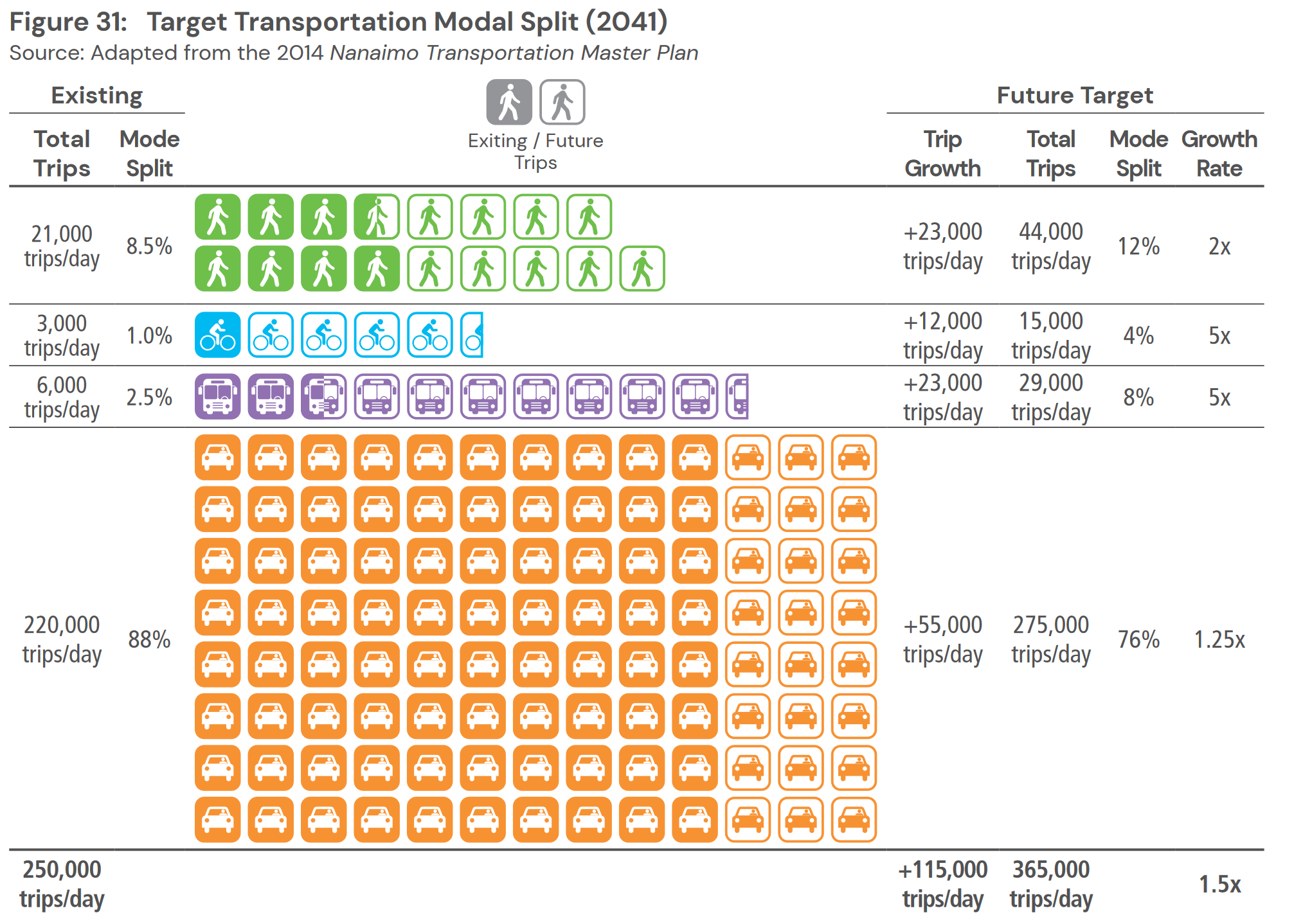

The average salary of a Nanaimo resident is roughly $41k pear year2. The CAA estimates the cost of owning and operating a car to be between $8k and $13k per year3, between 20% and 30% of the average Nanaimo resident’s income. The obvious solution to such an insane cost would be to take public transit. However, our city has sprawled out so much to where the RDN is unable to service the whole of Nanaimo with frequent rapid transit. All of this is reflected in the transportation choices of residents in town. Roughly 88% of residents drive as their primary mode of transportation4. “Auto-oriented communities present major barriers for residents who don’t or can’t drive, limiting their access to essential services and community and social engagement, which are critical to long-term health and wellbeing,” says Heather. She continues, “Residents most likely to be affected by this include seniors, youth, people living in poverty, and people with disabilities. Designing our neighbourhoods to be people-oriented instead of auto-oriented means leaving no-one behind while decreasing our transportation emissions.”

“The farther our homes are from our places of work, schools, and amenities, the more driving we all need to do and the more emissions we generate.”

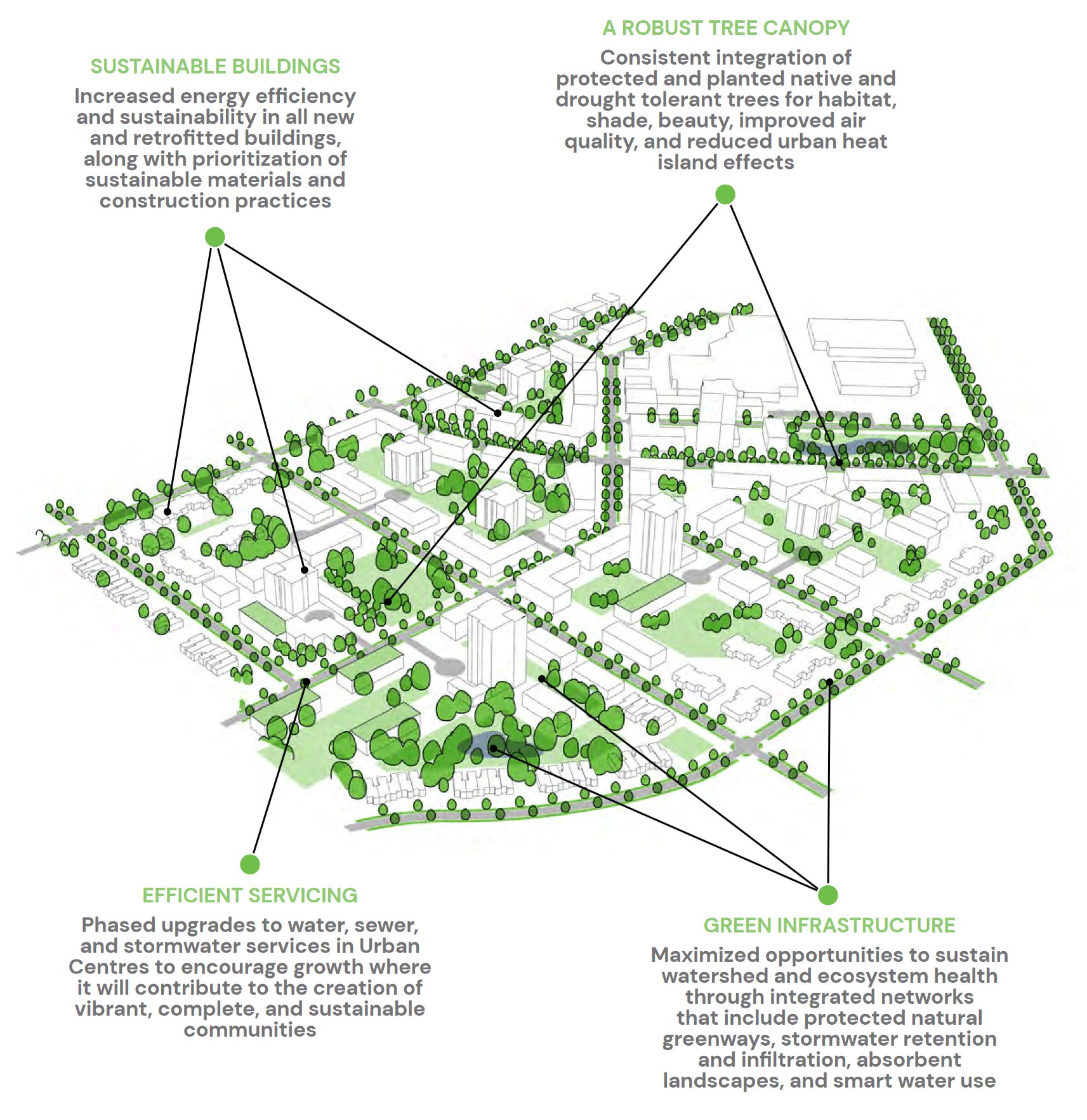

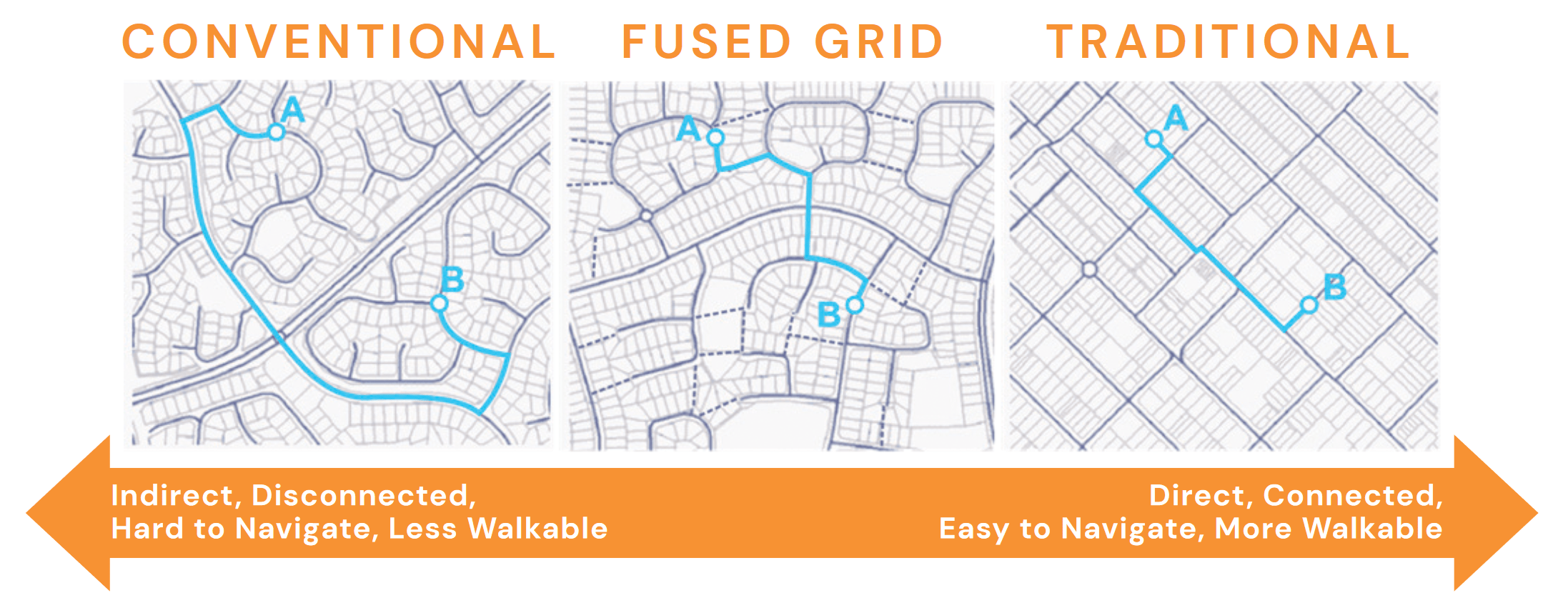

Because of the car, Nanaimo stopped being scaled for people and started being scaled for the car. This means that street blocks were larger, roads curved instead of forming a grid, giant parking lots were mandated on commercial and residential buildings, and more. Unlike other disciplines, urban planning can be incredibly tangible to people. If you take a walk downtown, you’re able to reach business, apartments, and parks with a reasonable level of convenience. You can’t say the same for the North-End, where massive swaths of single-family residential is segmented from all-consuming big-box retail chains laid along Island Highway. You don’t need to be an urban planning dilettante to know that one part of town was built for people while the rest was built for cars. This development pattern is at the heart of Nanaimo’s climate woes. When our homes, parks, and retail spaces are spread out, it becomes impossible to walk to them. Much of Nanaimo lacks safe, accessible cycling infrastructure and public transit, so residents are forced into cars. It’s not rocket science, it’s poor urban form.

Coincidentally, the parts of town that experience the highest degree of pedestrian activity are the parts that were built before the automobile. Harewood, downtown, the Old City Quarter, and the hospital district. You can split Nanaimo in two: a densely-built, grid-oriented bottom half and a windy, auto-oriented top half. You can predict how often someone drives based on where they live.

A massive hurdle that prevents the RDN from offering frequent and reliable public transit like those you see in Vancouver and Victoria is (you guessed it) sprawl. It would be easier to service Nanaimo if it lacked the heavily suburban North-End neighbourhoods of Hammond Bay, and Lost Lake. Those kinds of neighbourhoods don’t house enough people to financially justify transit routes. The existence of the 20 bus that services Hammond Bay takes service hours away from parts of town that do have the population to support transit, like Harewood and Brechin Hill. Heather highlights the potential for public transit to reduce GHG emissions in town “Smart design of public transportation services will play an essential role in tackling the climate crisis,” says Heather. “Well-planned urban density allows for a smaller number of high-frequency bus routes, reducing emissions and increasing convenience for riders.” The RDN is in a tight spot: they’re obligated to run lines to less-populous regions of town–indeed, there’s a philosophical debate to be had between the kinds of transit lines that agencies run and whether they service everyone terribly or whether they service the densest parts of town well. The RDN and BC Transit’s philosophy is a mix of the two, where denser parts of town are given faster, frequent routes while simultaneously providing less-frequent lines to rural and suburban communities.

“Well-planned urban density allows for a smaller number of high-frequency bus routes, reducing emissions and increasing convenience for riders.”

While the RDN has plans for streamlining transit connections in Nanaimo, it will always have to contend with the obligation to service the sprawling suburbs in the North. “The Regional District of Nanaimo’s five-year Transit Redevelopment Strategy lays out ambitious plans to increase service hours by 56% over 2019/20 service and nearly double the number of transit vehicles over five years,” says Heather. “This is a refreshing contrast to previous five years in which service hours decreased by 8% despite population growth of approximately 9% in the RDN. Those changes will help make transit a more appealing option for commuters. We also applaud the inclusion of digital on-demand transit for rural areas and the choice of electric vehicles when new vehicles are purchased.” Transit is a key tool in reducing GHG emissions. However, there’s more that can be done.

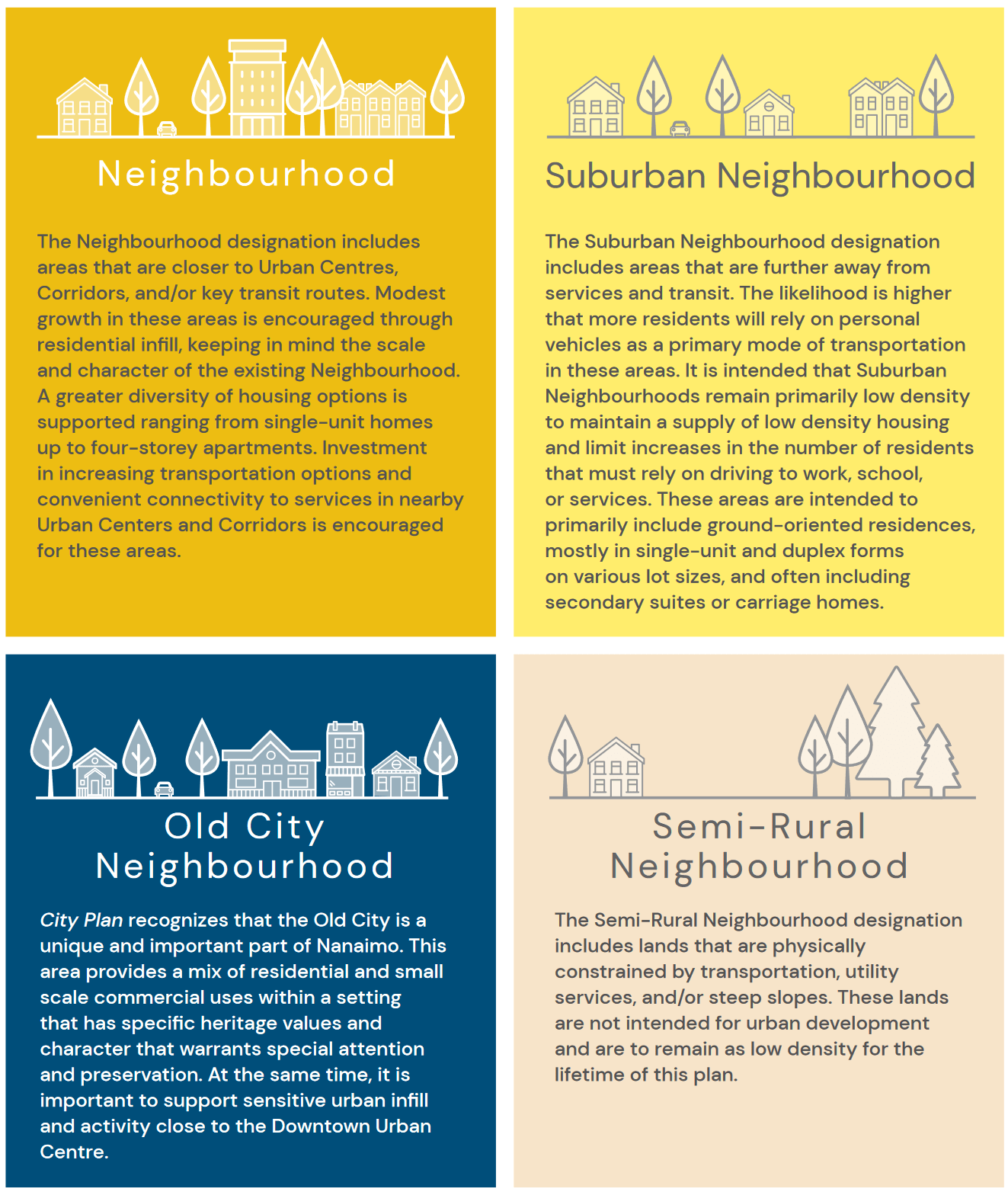

Improving neighbourhood density via infill is an important step towards remediating the auto-oriented design patterns of the past. By reducing the space between homes and shops, we reduce the distances people need to travel day-to-day. Those lucky to live by a corner store or a neighbourhood cafe already reap the benefits of this kind of urban form. It’s much faster and more convenient to run across the street to grab a loaf of bread instead of driving across town. Along with the tangible improvements of small-scale density, there are also immense climate implications. Heather puts it best, “Living closer together means preserving more land […], including old-growth forests that store over 1000 tons of carbon per hectare. Denser living also means we can live closer to our places of work, schools, shopping and services. This reduces our dependence on personal vehicles and makes it easier to use active transportation, benefitting our environment as well as our health.” She continues, “No matter how advanced our technology, our livelihoods will always depend on thriving natural ecosystems to supply us with oxygen, fresh water, and food.” As we sprawled out, we consumed more land. We’re now contending with the consequences of those decisions decades later.

It’s an uphill battle. From NIMBYs to climate-deniers, there’s no shortage of negativity and pessimism among Nanaimo residents. But there are also hundreds of passionate, committed change-makers and trend-setters eager to see Nanaimo flourish. Strong Towns Nanaimo tries to preach positivity, so we’ll leave you with this: at the intersection of climate and urban planning, you’ll find a resilient, financially-sound and beautiful Nanaimo. Us, and the Nanaimo Climate Action Hub, are working hard to improve the quality of life of residents and to engage in actions to mitigate the effects of climate change in our region. At the end of the day, people-oriented are what matter most.

A note about the Nanaimo Climate Action Hub: The Nanaimo Climate Action Hub was founded with the goal of advancing climate action in Nanaimo and the surrounding areas through advocacy, local initiatives, and collaboration with other organisations. They hope to continue improving how humans interact with the environment by connecting with passionate and diverse change-makers in our community. Visit their website.